Coral Skeleton

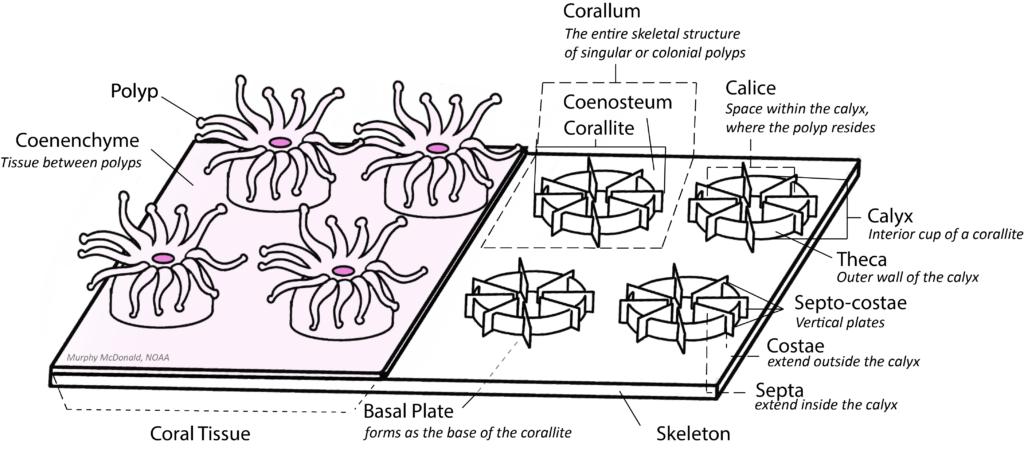

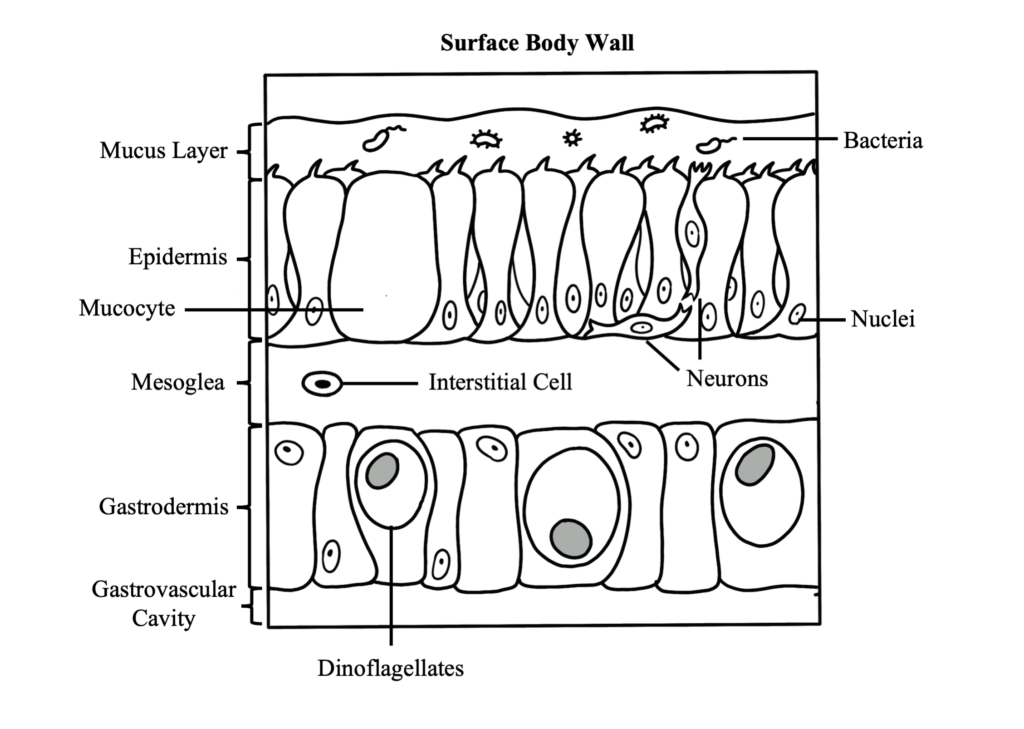

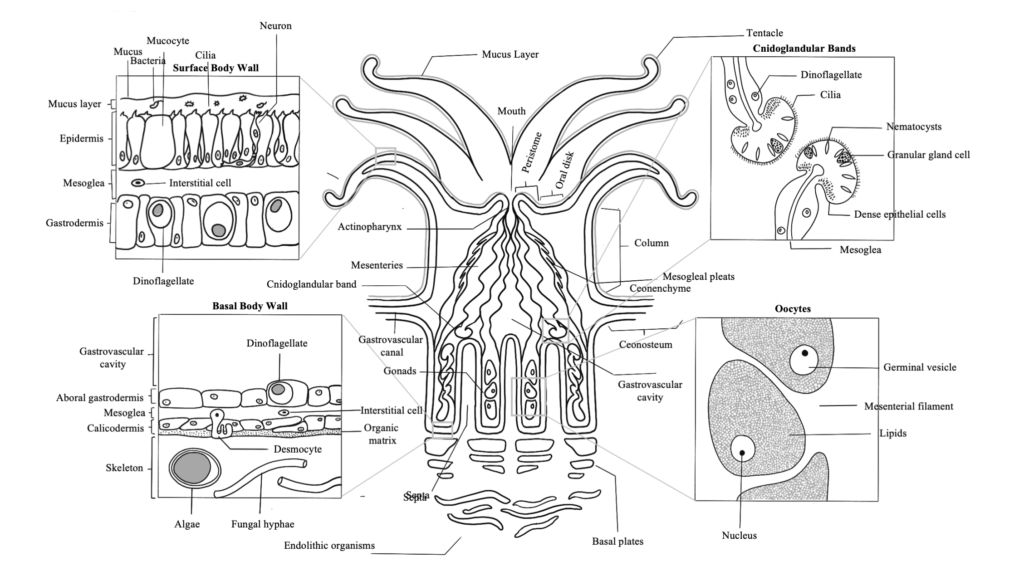

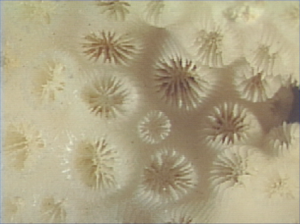

Coral skeleton is comprised of aragonite, a crystal form of calcium carbonate. The skeleton of each individual coral polyp is called the corallite, and the porous skeleton that links polyp corallites within a colony is called the coenosteum.

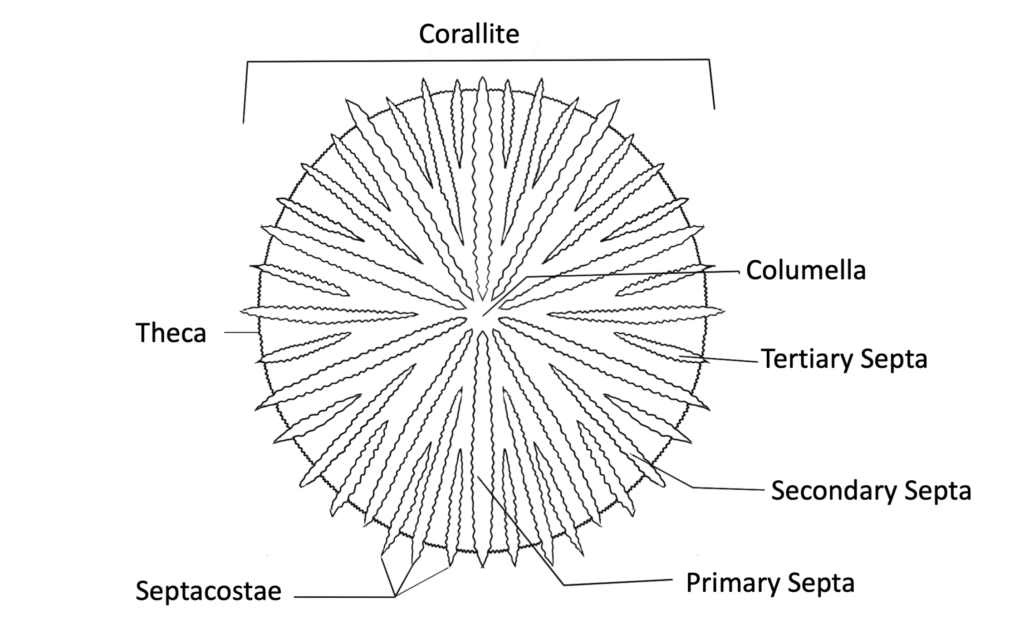

Each polyp sits with in the calyx, or interior cup, of each corallite. The calyx is within a wall called the theca, which is transected by vertical plates called septa-costae. The portion of these plates that fall within the wall perimeter are called septa, and the portion of these walls that extend beyong the wall to the outside of the corallite are called costae. Horizontal rods that form a lattice between septocostae are called synapticulae.

Septa within each corallate have a cyclical symmetry and can have varying lengths depending on the species (the longest being primary septa, then secondary septa, and tertiary, and so on, with decreasing septa length). In some species, these differently-sized septa can fuse at the ends to form a pattern called Poutales plan. Some septa can have projections on their interior margin called paliform lobes, which, depending on their height and definition, can form what is called a paliform crown around the center of the corallite, called the collumela. Septa are often lined with tooth-like projections that can have varying degrees of dention, ranging from finely serrated to jagged.

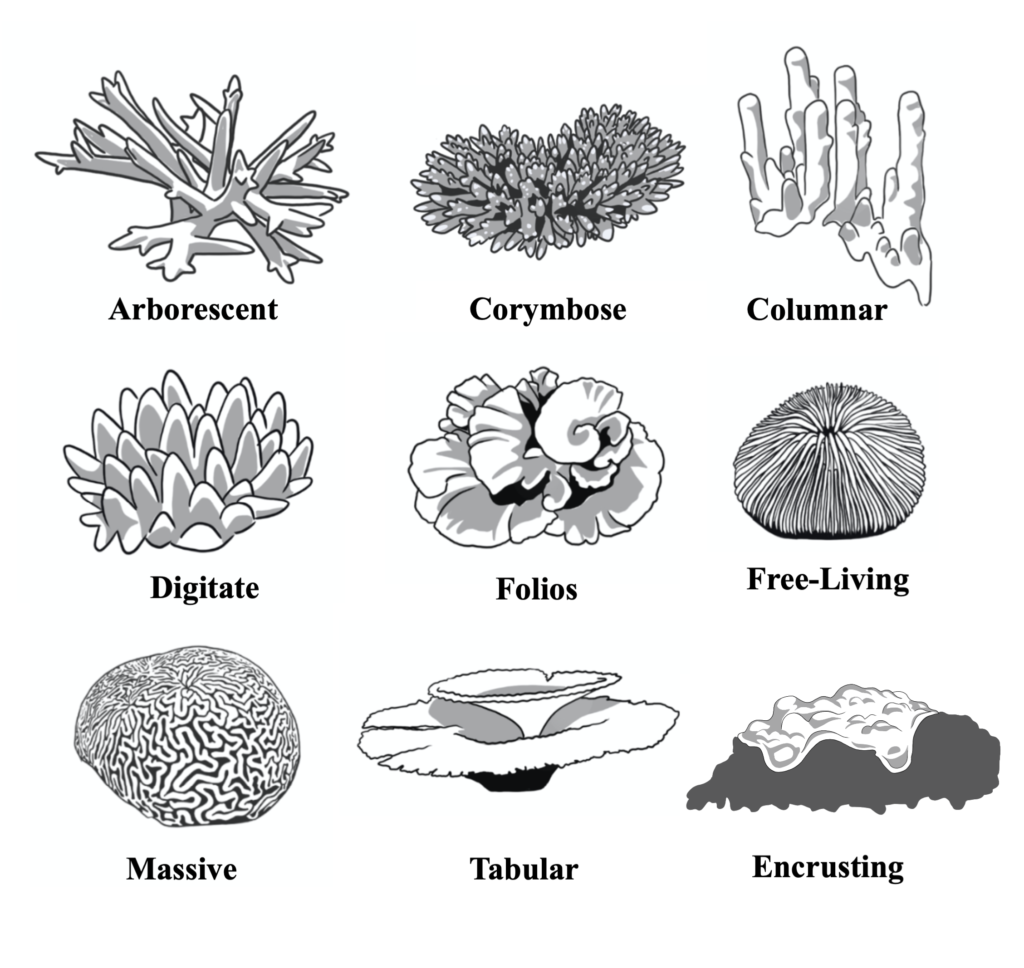

Corals can exhibit a range of corallite morphologies, and in many cases can have intermediate versions or combinations of two or more morphologies:

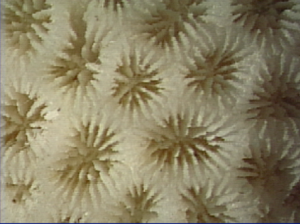

Plocoid

All individual polyps have their own wall

Cerioid

Multiple polyp corallites share a single wall

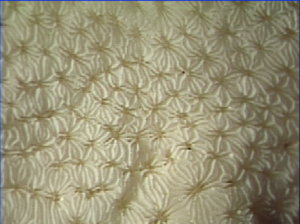

Themnasteroid

Multiple corallites share septocostae

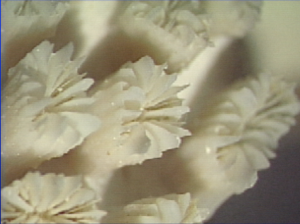

Phaceloid

The separate walls of polyps are tall and tubular

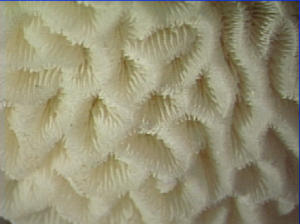

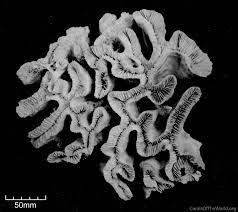

Meandroid

Polyps share corallite walls and form valleys

Flabello-meandroid

Polyps have their own corallite walls but are meandroid

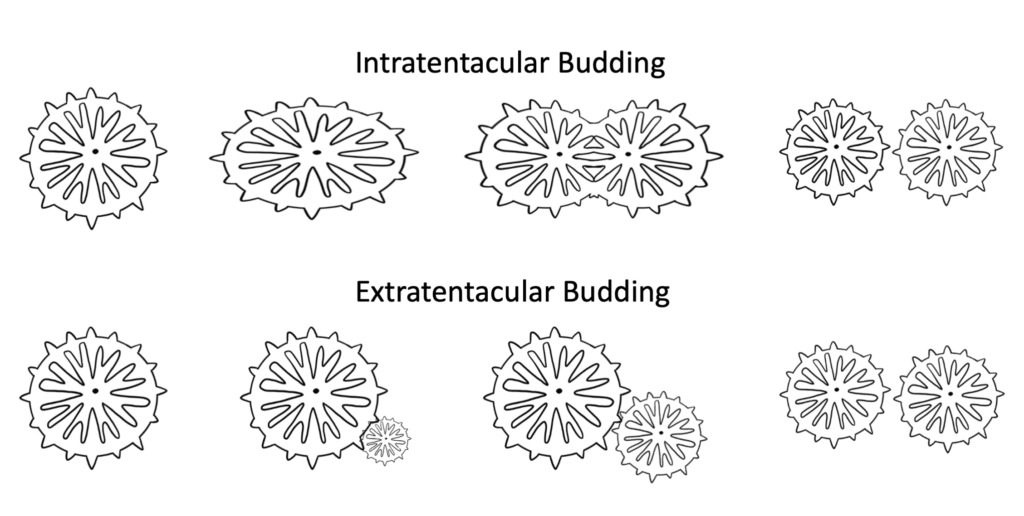

Coral colonies grow by adding new polyps through the process of budding, where a parent polyp is divided into two or more daughter polyps. This division can occur from within the ring of tentacles of the parent polyp, known as intratentacular budding, or can occur outside of the tentacle ring where the daughter polyp forms between existing polyps, known as extratentacular budding.

Learn More about the Essentials of Coral Biology:

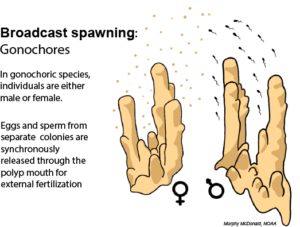

Coral Reproduction

Learn about how corals use different reproductive modes to overcome their immobility

Official websites use .gov

A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Official websites use .gov

A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States. Secure .gov websites use HTTPS

A lock or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS

A lock or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.